Are cinematic universes inherently bad?

Star Wars was sold to Disney in 2012, and the result brought that galaxy far, far away into the 21st century—specifically, it guaranteed that Star Wars would expand beyond Episodes I-IX in the Skywalker Saga and continue on and on into the future. No longer a singular modern myth, we will now be watching Star Wars at the cinemas seemingly until the end of time.

Not everyone is into that idea. But Star Wars is actually better outfitted for this future than most.

In a recent article in The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman bemoaned the how empty the Star Wars universe was becoming, citing William Gibson’s novel Pattern Recognition with its coolhunter central character Cayce Pollard, and her physical aversion to disingenuous, diluted branding. The article goes on to cite how the latest Star Wars offering—Solo—was a perfect example of the very thing that makes Cayce physically ill to observe: A film that feels like Star Wars, but isn’t truly. “When the universalization of ‘Star Wars’ is complete,” Rothman says, “it will no longer be a story, but an aesthetic.”

And this is funny to me. Because Star Wars has always been at least 90% aesthetic.

This is part of the reason why Rogue One was such an affecting film, even if its characters were too faintly drawn to make for deep cinema—director Gareth Edwards knew one thing better than most, that Star Wars is primarily a visual vernacular, perhaps even more than it is a story. You can look at Star Wars and know what it is without ever hearing a word spoken by a character. This is part of the reason why George Lucas’s scripts for the prequels were always so painful to hear out loud, and why those films fare better silently overall. Star Wars is a look, is a color palette, is a layer of dirt and grime. And if that’s not the entirety of it, that is certainly the core of it.

Now, to be fair, I also don’t think that Rothman (or the plethora of writers, fans, and enthusiasts who worry about the same issues where Star Wars is concerned) is wrong to be worried. He isn’t. Star Wars is in danger of becoming stale because the franchise is now owned by a big conglomerate corporation, and corporations don’t like risk or change or anything that will effect their ever-expanding profits. The truth of our near-cyberpunk future is that some stories are brands now. And brands shouldn’t be stories, even if there are weird examples where that has worked out in a company’s favor. Star Wars should not endeavor to be He-Man, or G.I. Joe, or My Little Pony, even if the majority of its money also comes from making toys that kids and adults want to play with, because it didn’t start as a toy. It started as an epic myth.

But there is a way to save Star Wars. And that way is down to something that its oft-maligned creator, George Lucas, frankly excelled at: kitbashing reality.

I have called Star Wars a behemoth of super-culture before, and it still applies. George Lucas didn’t create his funky little space myth from a few beloved tales and knick-knacks. Star Wars is a kitchen-sink, multi-media, ever-evolving sticky vortex of global elements. It’s far-reaching and always renewing when it’s done right. Star Wars should never empty out because you should always be topping it up with new ideas and new references and new culture. Star Wars isn’t really a single myth: It’s a scramble of art and existence and story.

That scramble doesn’t always work, and it can be horrifically damaging when done poorly, as is born out in several racist caricatures in the first Star Wars prequel alone: the faux-Caribbean shtick of Jar Jar Binks, the anti-Semitism of Watto, and the thinly-veiled Japanese corporatism of the Trade Federation in The Phantom Menace all serve as proof enough that these converging sensibilities can make for some very ugly storytelling choices without care and attention paid. But when it works? It makes Star Wars very different from all the other sprawling fictional universes that we have to choose from. Unlike Marvel and DC, who are determined to shove very specific character arcs from 75-plus-years worth of comic book history on screen, Star Wars doesn’t have to keep dipping into the same well, or even keep working from the history it has built. It can dig a brand new well. It can forego any references or familiarity because the galaxy is a gigantic place.

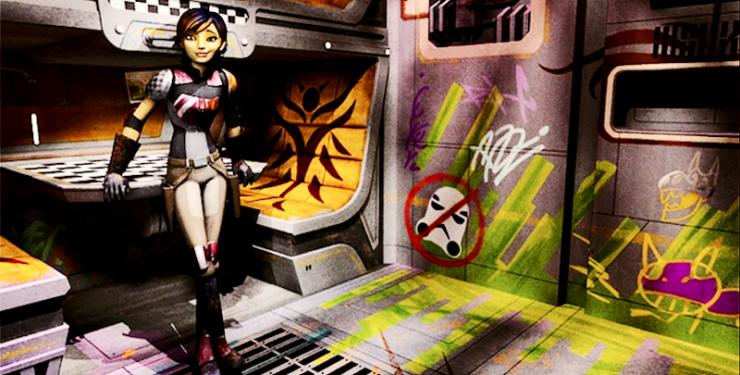

While the films may always be in danger of diluting Star Wars with style-over-substance in an effort to capture the largest audience possible, other areas of the universe have had no issue cultivating the ever-growing referential encyclopedia that makes the franchise enjoyable. The cartoons Clone Wars and Rebels, and the novels being produced by an endless array of delightful authors have never stopped doing what Star Wars does best—adding to the scramble. The references and influences continue to stack in these bright corners, a place where nothing seems off-limits. The Nightsisters are like the Bene Gesserit of Dune; queer characters exist and fall in love and get married; there is a Hutt crime lord who sounds like Truman Capote; the Toydarians (Watto’s people) are treated with respect; we find thriving guerrilla art touting the Rebellion’s cause; Alderaanians speak Spanglish—and all of this fits perfectly.

Buy the Book

Binti

Because it’s Star Wars. Everything belongs in Star Wars.

If the films want to avoid irrelevance, especially when held up to the rest of the ever-expanding Star Wars universe, they need to embrace that philosophy. Rian Johnson did this in The Last Jedi: Luke’s strange hermitage on Ahch-To and the pockets of culture we observe all over Canto Bight are a part of that scramble. The layers make the universe come alive in ways that it can’t if it gets bogged down in old-school sensibilities and old-school rules. Occasionally the other cinematic universes out there understand this and create their own scrambles—Thor: Ragnarok is a beautiful mash of Jack Kirby’s visuals, 80s film aesthetics, and director Taika Waititi’s heritage and sense of humor. Black Panther, of course, is another stunning example of using the previously tried and true formulas, and merging them with different histories, different aesthetics, different artistic frameworks to create something completely new.

And if it sounds like I’m advocating for diversifying the voices that create Star Wars stories by bringing that up, that’s because I absolutely am. What the Star Wars universe has achieved well in recent memory it has done by centering voices that understand the funkiness of the original narrative (in film and TV directors Rian Johnson and Dave Filoni) and new perspectives that bring exciting material we haven’t seen before (in novels from Daniel José Older, Claudia Gray, Chuck Wendig, and Delilah S. Dawson). If Star Wars is to maintain its scramble, it needs to nurture those voices and keep giving them the flexibility to futz with the dials, the tones and colors and sound balance that make up the series.

Solo has moments of this kind of inspiration: the plight of Elthree, the grotesqueness of Lady Proxima, the audacity of Lando’s gorgeous wardrobe. When it clings to those moments, the movie is delightful, but too much of the story veers from what’s unique in order to bring us the beats that will keep everyone comfortable. The Kessel Run is boring (and basically borrows a bad deus ex machina from 2009’s Star Trek in order to work), Tobias Beckett is an everyday rogue as stock as they come, Qi’ra and Han’s relationship has nothing to glue it together aside from a shared history that we don’t really witness. But the Star Wars cinematic universe is perfectly poised to avoid these pitfalls, so long as it trusts in what it already did well.

Mass appeal is a subsection of death, and we all know it. The best pieces of Star Wars have always been the strange bits; the often-imitated cantina scene, blue and green milk, two-headed aliens, spaceships that looks like criss-crosses and doughnuts. One of the greatest pieces of Star Wars fiction is a set of Clone Wars episodes that focus on Hutt politics! Let Star Wars be what it is. The mythological arcs may be comfortable, but we’re outside the core mythos once Episode IX is done. Go nuts.

When you trust the scramble, you don’t have to worry about Star Wars being empty. And then you can enjoy your cinematic universes well into the future. The only real question is whether or not one of the biggest companies in the world is willing to let Star Wars be what it is in the years to come.

Emmet Asher-Perrin demands more Hutt politics. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

” the faux-Caribbean shtick of Jar Jar Binks”

Somewhere, and I wish I’d gotten a copy of it, I saw a version where the character was redubbed with a standard sort of English accent, with similar diction, and that fixed so much that was wrong with it.

My own preference would’ve been to redub pretty much all of the aliens (Jar-Jar, Watto, the Federation guys, etc.) in subtitled alien-speak. And, while we’re at it, replace most or all of the battle droid voices with electronic beeps & boops.

I’ve never seen the dub that @1 mentions, but the voice actor who performs Terry Brooks’ Phantom Menace novel in audiobook tones Jar Jar’s accent down a LOT, and the character is at least 60% less annoying as a result. Anakin is also much better acted.

Star Wars was originally so great I think because it is a miracle that it worked at all–and that it still mostly holds up. They somehow bashed together a bunch of model kits and made spaceships that felt like they had some gravity. They kind of invented (read: stole) a cinematic way of making starships move around. They had a few ingenious shots that set the mood–the introductory crawl; the looming Star Destroyer; the twin suns.

More important still are the sounds I think. How did Lucas luck into both John Williams and Ben Burtt? It’s the sounds that really make me think of Star Wars–the sweeping faux-Wagnerian orchestras, the snap-hiss of lightsabers, the bloop of droids and the roar of Wookiees. The Prequels are terrible movies, but when they work it’s usually because the music and sound effects are working. The romantic scores can’t really make me believe in Anakin and Padme’s relationship, but that little violin solo in ROTS almost makes me buy the tragedy. The conflict between Jedi and Sith doesn’t make much sense, but the Duel of the Fates and Battle of the Heroes make me feel like something of substance is going on. Ultimately I think that killed Rogue One for me; not only were the characters boring and the story barely coherent, but it didn’t SOUND like a Star Wars movie. It was too different to feel appropriately Star Warsy, and yet not distinctive and bold enough to feel like a new direction for Star Wars either.

The other thing is novelty though. The original Star Wars films worked because there was nothing else like that at the time. They got away with a shallow pastiche because it was just wildly unlike everything else out there. Special-effects laden pastiches are everywhere now though. I think the challenge is both remaining Star Wars, and finding distinctive new things to do. The MCU has been making movies that often feel like they are in totally different genres or tones–going from The Winter Soldier to Guardians of the Galaxy in a matter of months. Can Star Wars do that? I guess we will see.

Star Wars is a pallet, with which an artist can paint any number of pictures, but it is one which naturally favors themes for related stories. Perhaps the biggest problem that the Disney SW films have run into of late is that it has not only rejected serial themes but outright tried to destroy them. Specifically, The Last Jedi not only failed to realize that it was part of the Skywalker Saga, but did its very best to undermine the very idea of a Skywalker Saga. Whatever its other qualities as a film, that simple failure on its part is most likely what left such a bad taste in the mouths of so many viewers.

Rogue One and Solo had the advantage of not being part of series. As one-offs, they had significantly more freedom than a numeraled Saga film, and in both cases they profited from it. Rogue One was able to embrace a more realist and military style without the mythic overtones and tropes of the Skywalker Saga, while Solo benefited from embracing both a western aesthetic and a crime theme that would not have been appropriate for a numeral film.

The prequels were generally bad films, but they were very consciously Saga films and at least tried to follow the themes of the overarching story with the rise and fall of Anakin followed by the rise, fall, and redemption of Vader. One of their biggest failings from a storytelling aspect was that they got too bogged down in the practicalities of trade and politics and lost much of the mythic tone of the OT.

For Star Wars to succeed going forward, Disney needs to remember one thing: leave room for myth. Failing to do so is what killed tLJ. Arguably, Solo’s weakest segments came about when the film tried to explain the myth of Han Solo (the Kessel Run comments, for instance). The Phantom Menace was at its worst when it decided to explain in minute detail how Jedi and the Force work (midichlorians are worse than Jar Jar in my book).

If Disney can avoid over-explaining legends and myths and can recognized that certain stories are best fitted by certain tropes and genres, then they can avoid the mistakes that have been slowly alienating fans.

Canto Bight was fine on its own. Though I wish they had saved it for another Star Wars movie. In the already overstuffed The Last Jedi, it didn’t need to be there. It’s like if Han and Leia went on a side quest to free some racing pterodactyls at the Bespin gambling hall or something before getting captured by the Empire. Yeah, that’s nice and all. It underlines that our heroes are heroes fighting for liberty, but it doesn’t need to be in this story.

If they wanted to show us war profiteering, there were simpler ways to go about it. DJ showing Finn the holograms for example.

While I love Rebels, I haven’t enjoyed any of the new novels, except those written by Claudia Gray. Part of that, I’m sure, is her novels are the closest in tone and spirit to the old EU. Old dog, here. The new tricks just aren’t doing it for me, I guess. But I don’t begrudge them to anyone else. Its not like I can’t pick up Heir to the Empire any time I want, and just pretend that the new movies are fictionalizations within that universe. Lol. The exact opposite of what I was hoping for when Disney announced the old EU was being rebranded as Legends.

I’m not sure why Solo merits a demerit in this case. Beckett may be a stock rogue, but has Star Wars had a quintessential rogue in the films before? Isn’t that kind of the point, here? Meanwhile, The Last Jedi engages in usual-elements just like the rest of the new films. They’re not all that different in that respect.

I’d also point out that the original film took some inspiration from Dune, so that’s been part of the scramble for a very long time.

@5 The Last Jedi would have been better if it had been a non-main sequence movie. If it had been a side story, then even it casually killing off favourites Like Admiral Ackbar would have been begrudgingly tolerated.

@6 It should have had Lando in it. The high rolling master hacker ought to have been Lando, then Rose and Finn could screw things up with the camelhorse race, get separated, and Lando get swept up with something else and they are left with the offbrand Lando who betrays for no real reason (unlike Lando’s supposed betrayal in Empire, which had actual reason to it) other than because the plot says so. That would have tied the Canto Blight segment more tightly to the rest of the movie too. It wouldn’t have seen so much like a pointless sidequest.

I walked out about halfway into Solo. Cast, script, directing, music, I mean, I don’t care if it is SW related – bad is bad. And the problem is that these are not supposed to be creative works for the generations – they’re meant to make money. That is all they are supposed to do. No one at the studio, even good ‘ol 20th Century Fox from years ago, gives a hoot about the fantastic stories or myths or whatever – they just care about the bottom line. If fans do their own stories they can keep some sense of quality storytelling no matter the storyline. They thought Ron Howard would deliver. Didn’t happen.

I have never watched a Star Wars movie that I didn’t like. Some are better than others, but they have all been fun. People who are picking the Star Wars movies apart don’t stop to think how good they are. I lived for many years when the only SF films you saw were mind numbingly bad. You kids don’t know how good you have it. You have a cornucopia of riches, and you do nothing but complain about it.

@11 How was there a time when the only star wars films were mindnumbingly bad? I assume you’re referring to the prequels, but similar to what Anthony Pero said, we can always just go back and enjoy the original trilogy and disengage with the prequels as much as possible.

Am I just tired and missing the joke? It’s always possible with m

@12, I believe @11 was saying that all Science Fiction films were bad, and that Star Wars changed things.

@13 Well, perhaps not ALL SF films were bad, but before the Star Wars era, the vast bulk of them were bad. And if you follow Keith DeCandido and his Superhero Rewatch, and look at the hideous movies that passed for superhero movies in the past, you will realize that there were not many good superhero adventures in the old days either (https://www.tor.com/series/the-great-superhero-movie-rewatch/). We are living in a Golden Age of geek cinema and TV. The glass is more than half full!

Something I’ve learned to appreciate about the expanding universe of Star Wars is that you can introduce a whole new host of alien races nobody’s ever seen/heard of before, and nobody blinks. Star Wars is endlessly diverse. Try that in Star Trek and the never-before-seen race needs a whole backstory to be slotted in. Star Wars? Nope, here’s another two dozen you’ve never seen before, no time to explain, move along. And the funny thing is, this used to irritate me.

Re music being at the core, there’s a Tor article waiting to happen about John Williams’ announcement that Episode IX is his final contribution and what this is going to mean.

it can survive by going back to the original timeline and making Legends material.

Definitely wasn’t wearing my glasses and read SF as SW. Womp!

Star Wars problem is that the basic story has written itself into a corner. It was one thing for the Empire to have become so dominant once but then to come back to the story and find the Empire has rebuilt a n d is still bigger, better organized and overall more supported says that something is basically not being honestly reported. In literary parlance, are the Star Wars movies being presented by an ” unreliable narrator “? I think this is greatly a part of why audiences did not go out to the last Star Wars movie. And ,no, I do not at all agree Star Wars is a palette or a visual. Star Wars is a story of good vs evil. But, when the supposedly evil keeps being more functional over and over ( at the end of the last episode before Solo, the Resistance is 4 people and the light side has essentially burned itself and it’s heritage) where does that leave the audience?

Reading this piece and the comments that followed, I kind of had a semi-revelation – one of the reasons that the original trilogy worked and the prequel trilogy (sorta) worked was that the movies were essentially telling a story with an object (bringing down the Empire and the fall of the Jedi, respectively).

TFA also looked to do that, but TLJ basically delivered a giant f*** you to all of that.

While one might look at this as positive – it cleared the decks for storytelling sans baggage – I view it more negatively as it effectively left the movies rudderless and with no clear objective/ path ahead – LoTR has the destruction of the Ring, Harry Potter the defeat of Voldemort, Wheel of Time the defeat of the Dark One, et al.

As a viewer, I am invested in a continuing saga when I have a general sense that the series is building towards something – the fun lies is knowing how we might do that. Rogue One had that, Solo mostly not (I mean, Han’s backstory while cool because of love for the character, is essentially without defining consequence, really).

Kartikeya @@@@@ 19 – agree with that. I remember the day I came back from cinema after seeing TLJ. My roommate enjoyed it and I…didn’t. I was struggling to put into words why I didn’t like it and I remember eventually expressing the thought that I simply didn’t understand where the story was going. What story were they trying to tell? There were many other things about the movie that I didn’t enjoy, but that was definitely something that stood out to me. I didn’t sense a clear mythic arc for this movie(trilogy really!) and the lack of that has hurt my enjoyment in these films, to be sure.

@18

I feel like you and Emily are both right here. Star Wars is a story of Good vs Evil, but it is told chiefly through visual cues (and the brilliant score). Not just because film is by nature a visual medium, but because Star Wars has always been better at showing than telling.

The Falcon is immediately recognizable as “a hunk of junk” because we can compare her to the imperial star destroyers which are sleek and shiny. We don’t have to be told anything about the quality and expense of spaceships.

Good and Evil both have a color palate and imagery that informs how they function. When you see the rebellion in a meeting, they’re all clustered together, leaning forward, you get the sense of warmth and mutual purpose. When the grey-suited admirals have a meeting, they take up the same amount of space with fewer than half the people. They’re separated by a table, they lean away from each other to show fear and antagonism within their ranks.

That’s one reason TLJ didn’t work for me – it used SW visual cues to tell me that it was a Star Wars movie instead of using them to support the story. A single shot of young Ben leaning away with his arms crossed, closed off from the rest of his Jedi class would have communicated much more than “I could sense darkness in him” or whatever un-memorable voiceover we had.

@19 and 20

Agreed! I read an article where Rian Johnson admitted they don’t have an overarching plan for the current trilogy and that JJ might decide to go back and essentially reverse some revelations in TLJ (namely that Rey isn’t biologically related to anyone in the original trilogy) and I was just like THAT’S THE WHOLE PROBLEM. If neither JJ nor Rian Johnson knows what the plot arc of the trilogy is supposed to be, how are they supposed to make films that fit together?

@20 and @21

It’s really quite disappointing that they don’t have an arc in mind. I suppose that’s part of Disney’s overarching plan to have episodic entries, without giving any one person(‘s vision) a chance to jeopardise the assembly-line if said person leaves.

If so, they might do well to learn some lessons from the big daddy of episodic universes – the MCU. While the MCU has certainly sacrificed individual creativity (Ant-Man being the obvious example), it still has a captain at the helm – Feige – who ensures that each individual story-line, no matter how removed from the other entries, is building towards a definite end (not ‘the end’, but certainly ‘an end’).

SW needs a Feige (until now I had thought it was ol’ JJA – that’s gone outta the window).

As somebody who also worries a bit about ‘Star Wars’ fatigue, I do get the concern over too much, too fast. I don’t want a bunch of stuff that just feels like everything else out there. I think you’re onto something regarding the mixing of cultures and tropes and stories (kind of like Wheel of Time, in a way) – and I also love the weird bits. I loved the books (and still love the books). I’ve really enjoyed the TV shows, even if not every element was to my taste – that was okay, because it’s a big galaxy. But I think the books were a huge part of that for me. There were military fiction style books about the X-wing pilots. More mystical books about the Jedi. Heist or investigation books about the seedy underside of things. Books about the clones, the bounty hunters, the Sith, the Jedi, smugglers/gangsters. Yeah, there were also some kind of crazy ones (I’m looking at you interdimensional being in Crystal Star) but in a way it added to the charm. Heck, even though it’s not really my jam, there were even books about zombies.

I’m finding that I am enjoying the one-offs and TV series more than the sequels; in part because I am a little too invested in the main saga and would have preferred they left it alone, but there are things I enjoy about those as well. Like AlanBrown @14 says – it’s not all to my liking, but I AM thrilled that we’ve got so much to choose from.

All that said I agree with both Emily to an extent about the importance of the visuals and broad strokes, and the others who have mentioned that it’s not JUST the visuals – there IS an important mythic arc and thematic sense to the original trilogy, and that’s in part why the sequels can feel unsatisfying for me at times. Where is it heading? Do they even have an arc? Don’t get me wrong – TLJ raised interesting/poignant themes but I don’t love all the ways it was executed.

@@.-@ – I am so with you here on the sounds and music. And I love the prequels but I know a huge part of it is in fact because of the music and visuals. I think I just don’t have the same ability to evaluate acting/dialogue as other people but music is one of the few things that really moves me. So experiencing the prequels for the music was for me, in some ways, enough.

You 100% lost me with your comments on the Rogue One scorethough. From the first note of the score it sounded like Star Wars to me. Aside from the obvious references to things like Imperial Attack, the main theme, the Force theme, the spaceship fanfare, the Imperial March, it even brought back some of the 1977 motifs. Jyn’s theme is built around an obscure phrase of music playing in ANH while Obi-Wan muses about the message in Tales of a Jedi Knight/Learn About the Force. The song Star-Dust incorporates the opening and the flute lines from ‘Hologram’ becuase it plays during the scene with Bohdi and the message is revealed to be in the cell behind them. I think Krennic’s Aspirations aslo has shades of a Revenge of the Sith inspired theme as well for the Mustafar establishing shots. There were a lot of clever things done with that score in a short time. (That said, Powell’s Solo soundtrack was also amazing and in terms of action cues and high energy has a lot going on there…)

@5 – have to admit, I love the midichlorians (used to be a microbiologist) and if there’s a problem, it’s that nothing really came of it. The Clone Wars (and some of the old EU) did more with it that I think could have been quite interesting. Apparently GL’s script which was recently revealed (and most people are saying would have been awful) also was going to have something to do with it (and I expect tie in with the arc in Clone Wars season 6). Thing is, while it sounded weird (and I certainly would have wanted somebody else on board to rein him in in terms of directing, script, etc), I couldn’t help but think – at least that sounds DIFFERENT! I think some interesting directions, especially regarding the Force, could have come with that. But myth and mysticism and science don’t always have to be at cross purposes. However, I do kind of agree about Solo – I did enjoy it, but like the Boba Fett film, it wasn’t something I was craving – I don’t need to see the backstory for every cool/mysterious character. But on the other hand, it can be fun to see how that myth originates, as well as the wider glance at the universe it gives us.

I love this article because it pretty much nails to me what is the fundamental appeal and joy of Star Wars in that It’s a Universe of endless wonder and imagination where anything is possible (very important to a 10 year old that).

There is a balancing point between delivering something new and continuing what went before however. I think that this was the problem with The Last Jedi away from the knee jerk reactions of the Luke fans. The penultimate story of a saga is not the place to redefine the saga and introduce new elements that renew the brand (which is what I assume The Last Jedi was trying to do) it is supposed to set up the events of the final act of the Saga. This is what The Empire Strikes Back did so well and why it is cited as being the greatest sequel of all time. It takes what has gone before, expands on it while introducing a more in-depth aspect to what we think we know while setting up the events that lead to the conclusion of the story.The Last Jedi really didn’t seem to fulfill any of this to me and that’s why it is the least favourite of all the Star Wars movies for me, Ep II for all it’s faults did start a war after all.

Cue the outrage.